Recalling Jenkins Raid and the Confederacy coming to Meigs County

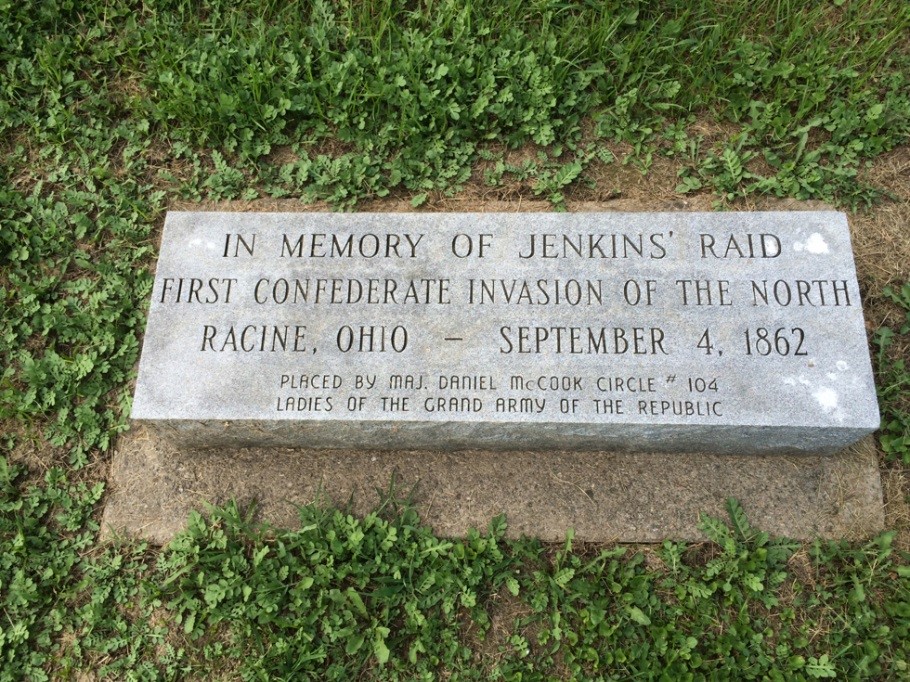

Memorial in Racine, Ohio at Star Mill Park. Photo by Jim Freeman.

If you have lived in southeastern Ohio for any length of time, you have probably heard of Morgan’s Raid through Indiana and Ohio during the U.S. Civil War. However, most people are unaware of the OTHER Confederate Invasion of Ohio, one that preceded Morgan’s Raid by roughly ten-and-a-half months, and one that took place right here practically in our backyard.

Confederate Brigadier General Albert Gallatin Jenkins’ Western Virginia Raid started Aug. 22, 1862, in Salt Sulphur Springs and concluded 21 days later at Red House on the banks of the Kanawha River. The bulk of the raid was conducted within the present-day state of West Virginia with one exception: the evening of Thursday, Sept. 4, 1862, a portion of his command crossed the Ohio River into Ohio and briefly occupied the town of Racine before crossing back into Virginia.

Why does it matter? When you look at the U.S. Civil War, you see that most of the fighting was done in the southern states that seceded from the Union, or in those “border” states, which remained in the Union despite being states where slavery remained legal. Uniformed Confederate incursions into actual northern states were rare. Racine was the second northern town to be occupied by Confederates during the Civil War, and the first in Ohio.

There are few historical markers to commemorate Jenkins Raid in Ohio, and none that mark the route taken by the 8th Virginia Cavalry Regiment in its ride across southeastern Meigs County.

Jenkins’ Raid – Sept. 4, 1862

The Confederacy Visits Meigs County

Prelude

It was high summer in Meigs County, Ohio, and the oppressive heat of the past two months lingered on. Most of the local crops were harvested for the season and those farmers that remained (those that had not gone off to war) were busy preparing for the upcoming winter – heralded by the hickory and buckeye trees, which were already turning yellow and dropping leaves.

Although the Confederate state of Virginia lay just across the Ohio River, the fighting in the War Between the States seemed far away for the farmers and their families in this corner of Meigs County. However, events were unfolding that would soon bring the war right to their doorstep.

The morning of Thursday, Sept. 4, 1862, saw a force of roughly 500 Confederate cavalrymen under the command of Brigadier General Albert Gallatin Jenkins gathered in Ravenswood, Va. They had just ridden hard from Ripley, Va., and their next destination was the Mason County Courthouse in Point Pleasant, Va.

Ravenswood of 1862 was substantially smaller than it is now, mostly contained in an area between what is now Sycamore and Gallatin streets to the north and east, and the natural barriers of the Ohio River and Sandy Creek to the west and south. Jenkins and his men spent most of the day resting there in Ravenswood, enjoying the hospitality of Southern sympathizers, only occasionally harassed by Union soldiers and militia shooting at them from the Ohio side of the river.

The break allowed the hard-riding Jenkins and subordinate officers to discuss their next move.

Jenkins stood about 5-foot-10 inches tall, and according to a southern newspaper correspondent, was “well-formed and of good physique; dark hair, blue eyes, and heavy brown beard; pleasing countenance, kind affable manners, fluent and winning in conversation; quick, subtle, and argumentative in debate.”

At 31 years of age Jenkins was clearly an uncommon man with a lifetime’s worth of accomplishments. A Harvard-educated attorney, he had served as delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Cincinnati in 1856, was elected twice as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives, declined a third term and served as a delegate to the First Confederate Congress and was now a brigadier general of cavalry.

The slave-owning, aristocratic Jenkins owned the sprawling Green Bottom plantation along the Ohio River north of Huntington, Va. (The plantation house and a historical marker exist today along WV State Route 2 north of Huntington.)

It was hot that afternoon. Jenkins paused for a moment, pulled out a handkerchief and wiped the dust and sweat from his brow and appraised the low hills of Ohio, which represented the homeland of his adversary.

The past couple of months had been good ones for the Confederacy and for Jenkins – the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under the command of General Robert E. Lee had recently crushed the General George Pope’s Union Army of Virginia at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Confederate General Braxton Bragg had just invaded Kentucky, and Confederates were now roaming freely through western Virginia.

Jenkins and his men had been busy the past few weeks, raiding deep into Union-occupied Virginia and threatening the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. This very morning Jenkins’ men routed the force of some 200 federals in Ravenswood making them retreat across the Ohio River.

According to reports, by this point in the raid, Jenkins’ men of the 8th Virginia Cavalry Regiment had captured and paroled 300 prisoners of war; killed, wounded, and dispersed about 1,000 of the enemy; reclaimed to the government of the Confederate States of America about 40,000 square miles, then in the possession of the enemy, destroying many garrisons of home guards and the records of the Wheeling and Federal governments in many counties, and, after arming his command completely with captured arms, destroyed at least 5,000 small-arms, one piece of cannon, and immense stores.

So what thoughts entered Jenkins’ mind as he looked across the Ohio River? He was certainly aware of the political and symbolic significance of crossing into Ohio. As a leader, he knew that many of his men (including himself) were chafed that their homes were currently under Union occupation, and that “invading” the enemy’s homeland would have a great effect on their morale.

He could also see that going directly across the “boot” (the boot-shaped curve in the Ohio River) from Ravenswood, Va., to Racine and then back into western Virginia was not totally unfeasible. Weather-wise, conditions were almost ideal for fording the river, which was too low for Union gunboats to navigate.

Jenkins knew that Federal soldiers and Home Guards had given his men little trouble. Morale was high, bellies were full, and the horses rested and well-fed. He also considered the terrain they would cross, the expected conditions of the roads, the weather, sunrise and sunset, moonrise and moonset, illumination, and the amount of time they had remaining that day.

A good commander intuitively considers the mission variables that today would be described using the acronyms METT-TC and OAKOC: METT-TC for Mission, Enemy, Terrain, Time, and Troops and Civil Considerations; OAKOC for Observation and fields of fire Avenues of approach, Key terrain, Obstacles and movement, and Cover and concealment. Only after considering these variables did Jenkins decide that crossing this small portion of Ohio was a prudent risk.

The plan came together in his mind: cross into Ohio just before sunset to make use of the remaining light, then ride across the bend and into Racine under cover of darkness, and then use the darkness to screen the crossing back into Virginia.

Jenkins reasoned that he could safely split his force, sending roughly 150 of his men down the Virginia side of the river. The remainder, some 300-350, would cross the Ohio River (with the assistance of a local guide), ride across the inside of the bend, then re-cross the river at Racine before rendezvousing with the first group near Point Pleasant.

Jenkins also correctly assumed that his regiment could be in and out of the state, which had supplied so many soldiers to fight the Confederacy, long before anyone could organize a defense or engage them.

Thus decided, Jenkins turned about and issued the orders to his company commanders and they to their own waiting men – “Get ready to ford, we’re moving out.” Shortly thereafter, the larger group mounted up and headed out, crossing Sand Creek (as Sandy Creek was known then) and heading towards the riffle downstream of its confluence with the Ohio River.

The Invasion Begins

“About an hour before sunset I crossed the Ohio with the larger portion into the State of Ohio, losing one man by being drowned,” Jenkins wrote. “The ford was deep and the bar upon which we were compelled to cross narrow, and a number of the horses got into swimming water, but no other loss occurred except the one referred to.”

Today the state boundary between Ohio and West Virginia is generally considered to be the low water line of the Ohio River, and for day-to-day administrative purposes that definition seems to work just fine, but it isn’t necessarily accurate. USGS topographic maps show the actual state line just downstream of Ravenswood represented by a dashed line extending far out into the Ohio River almost to the West Virginia side.

When Ohio became a state in 1803, the river bank wasn’t where it is now – that was long before locks and dams raised the water level in the river and “locked” the river into its current location. In the 1860s there were many more islands in the river, along with shifting sand and gravel bars, riffles, fords, and waterfalls, most of which are now underwater.

The bar crossed diagonally towards an area still identified on Google Maps as “Sand Creek Bar.” In 1862 this may have been an actual island. A look at river maps from 1877 and topographic surveys from the early 1900s were also helpful in locating the crossing site. The “Welcome to Ohio” sign on the U.S. 33 Bridge is probably more representative of where the 8th Virginia Cavalry Regiment (CSA) scrambled up the riverbank into Ohio.

As many combat veterans can tell you, there is something electrifying about crossing into enemy territory. Your senses are heightened and your mind races trying to focus on every little detail that can possibly forewarn of danger; adrenaline flows and your pulse races. It’s almost narcotic and addictive – you never feel more alive. Certainly, this is how Jenkins’ men felt as they crossed into Ohio.

“The excitement of the command as we approached the Ohio shore was intense,” Jenkins reported, “and in the anxiety to be the first of their respective companies to reach the soil of those who had invaded us all order was lost and it became almost a universal race as we came into shoal water. In a short time all were over, and in a few minutes the command was formed on the crest of a gentle eminence and the banners of the Southern Confederacy floated proudly over the soil of our invaders.

“As our flag was unfurled in the splendors of an evening sun cheers upon cheers arose from the men and their enthusiasm was excited to the highest pitch.”

Captain John Preston Sheffey (cited in Soldier of Southwestern Virginia: The Civil War Letters of Captain John Preston Sheffey, edited by James I. Robinson, 2007) recalled that on Wednesday, Sept. 3, they set out for Ripley and confiscated $7,000 in Yankee money, then the next morning dashed on towards Ravenswood at a “regular sweeping Jehu charge.” He added that most of the Yankees in Ravenswood were able to escape across the Ohio, while others were taken prisoner.

“From the Ohio side they kept up a constant fire upon us for a while, but we soon made them run back among the hills,” he wrote. “One of our men was wounded quite seriously. According, we determined to drive them from their position.

“Flushed with victory, fat and hearty, we were conceited enough to attempt anything… We, the invaders, with colors flying, marched through the land of the Philistines in triumphal procession.

The Confederate “Invasion” of Ohio had begun.

Upon reassembling on the Ohio side of the river, and scattering a few Federal soldiers, Jenkins and his men saw a landscape much like what you would see today. Ohio was largely deforested by that time and most of the flat, level ground was in crops. Since it was early September, most of the produce would have been harvested with the exception perhaps of field corn and hay still standing in the fields. The road was lined with smaller fields, pastures, and orchards, that were broken into manageable sizes between 10 and 40 acres with brushy fence rows dividing them – barbed wire hadn’t been introduced yet, and weeds were rampant. Those farmers who didn’t have barns simply stacked their hay around poles in the hayfield.

The road along the river was dusty and comprised of hard-packed earth. Old maps show the road from Ravenswood to Racine closely following that of present-day County Road 338 (Great Bend Road) along the Ohio River to the crossroads community of Great Bend, then striking out overland along what is now County Road 124 (Tornado Road) eventually coming out in Dorcas, then making a series of right-angle turns (that no longer exist) at Beavers Corner before arriving in the village of Racine.

As men and horses headed northwest across the Great Bend, they passed a schoolhouse near the 90-degree turn in Great Bend Road, then passed the Great Bend Methodist Church a mile-and-a-half after that (where Bicknell Cemetery is located today). Continuing along they crossed Silver Creek and then Granny Run before the route turned more gradually westward.

As they rode, the open fields and pastures along the route eventually gave way to steeper hillsides, hilly pastures with brush and patches of woods. They left the Ohio River behind; Oldtown Creek was at their left flank first, then Yellowbush Creek as they crossed over the hill dividing those drainages. Along the route they passed two more schoolhouses, and as they neared Racine, the terrain leveled out somewhat and was characterized once again by open fields and pastures.

The Confederate cavalrymen were impressed by what they saw. Sheffey wrote: “Ohio is a beautiful land, and well is the river that rolls there, called ‘La Belle Riviere.’ Now along the splendid turnpikes of Miegs (sic) we cantered gleefully. On every side were the evidences of prosperity and affluence. The elegant mansions, the wildernesses of corn, the immense wheat-ricks, the tremendous oat-stacks, and the barns crammed with the golden treasures of harvest, all told us how little that country had suffered from fire or sword or any of the ‘dogs of war’.”

The Meigs County citizens were terrified, according to Jenkins, and clearly expected the worst.

“Women inquired for officers wherever our troops appeared, and, having found them, begged them not to permit them to murder them. Others came out of their dwellings and urged as a reason for our not burning them that they contained invalids too much afflicted to be removed,” Jenkins wrote.

“To these requests we replied that, though that mode of warfare had been practiced on ourselves, though many of the soldiers of our command were homeless and their families exiles on account of the ruthless warfare that had been waged against us, we were not barbarians, but a civilized people struggling for their liberties, and that we would afford them that exemption from the horrors of a savage warfare which had not been extended to us.

“It was manifest that they had not expected such immunity, and could scarcely credit their senses when they saw that we did not light our pathway with the torch.”

Some Meigs County residents were apparently not too proud to temporarily switch allegiances to protect their homes. “On more than one occasion, however, our presence produced a different effect, and the waving of handkerchiefs showed that the love of liberty and the right of self-government had still some advocates in a land of despotism,” he reported.

“It was a curious and unexpected thing to hear upon the soil of Ohio shouts go up for Jeff Davis and the Southern Confederacy. This was usually, however, in isolated spots, where there were no near neighbors to play the spy and informant,” he added.

“It was a subject of the very greatest interest with me to observe the state of feeling in Ohio and the impression our presence would produce. I may say in brief that the latter was characterized by the wildest terror – so much so that but for the pity for the subjects of it one could only view it as an absurdity.”

Since it took about three hours for Jenkin’s men to cross the Ohio River and travel the 11 miles across the bend, these interactions with the local populace were necessarily brief and didn’t slow the column much at all. A few mongrel dogs protested the invasion by coming out and barking at the parade of riders.

The Occupation of Racine

In short order, the riders entered Racine from the east, crossing the headwaters of Wolf Run and cresting the small rise where Tyree Boulevard is located today. Although Racine may have been called the Paris of Meigs County back in the day, it was nonetheless a much more compact community than it is now. Most of the town at that time was located between Fifth, Elm, and Vine streets, and the Ohio River.

According to the Pomeroy Telegraph of Sept. 11, 1862, it was around 9 p.m. when the party entered town.

According to Jenkins, upon “taking possession of Racine” they “put to flight” some of the local Home Guard who had assembled for its defense. Web-based astronomical sites show that Jenkins’ men entered Racine by the light of a waxing gibbous moon, which was nearing meridian height providing roughly 86 percent illumination.

What happened next, and if whether anyone was killed or not, is a subject of some debate.

The Pomeroy Telegraph, which for some reason buried the news of the event deep within its pages the following week, states that the raiders “shot a deaf and dumb man who could not hear an order to halt, and it is said wounded one or two others.” An opinion piece in the Wheeling Intelligencer cites the “shooting of an unoffending deaf mute near Racine.” Reports of the time were notoriously inaccurate and sensationalized; “fake news” is hardly a recent phenomenon.

It is not unlikely that a few members of the Home Guard were wounded in the process of being “put to flight.” It is possible since many Home Guards were men not otherwise fit for regular Army duty, but that would hardly count as an atrocity since they would be considered “fair game” as armed combatants.

Sheffey in his account wrote “a little before midnight, we reached the town of Racine. Here our advanced guard killed two Yankees and took five prisoners. One of our men was dangerously wounded.”

So, depending on what source one chooses to believe, except for the drowning victim, nobody was killed, or two people were killed and five taken prisoner, or a deaf-mute man was killed and maybe two others wounded. In any event there are no known gravesites of people killed in Jenkins’ Raid in Meigs County.

The riders proceeded down Elm Street and stopped at the gigantic elm tree growing at the corner of Third and Elm streets. The horsemen were awed by the massive tree, easily the most conspicuous landmark in the entire town.

Jenkins gravitated towards this tree, stopped, and then directed his company commanders to post sentries to prevent people from entering or leaving town.

The Elm Tree, according to a historical marker, measured 28 feet and 8 inches in circumference three feet from the ground, or nearly nine feet across, which would easily make it one of the largest elm trees in the country ever recorded before or since (it is hard to be sure because trees are usually measured at breast height or 4.5 feet).

In the mid-1800s, rural people were much more attuned to the natural light cycles of sunrise and sunset, moonrise and moonset; what artificial light that existed at the time was dim – firelight, lamplight, candlelight. In short, it got dark when the sun went down, the sort of darkness one rarely see these days.

Adding to the confusion, the darkness concealed the exact number of raiders. There was no visual spectacle of hundreds of riders sweeping into town; there was merely a cloud of dust, the smell of horses and their riders, the creaking of leather and the occasional clanking of rifles and other paraphernalia. There were men’s voices, some with the inflection of command, and it wasn’t conspicuously apparent just who was in charge.

According to reports Jenkins established the terms of the occupation and threatened to burn the village if the townspeople resisted.

The riders scattered throughout the small town looking for horses or other valuables, but left people, their homes and businesses alone – the village was not ransomed, looted, burned or destroyed.

Apart from the insult and indignity shown in occupying the little town, Jenkins and his men exercised great moderation of conduct for that time and place. As a politician and a man born to leadership, he no doubt understood the importance that impressions can make and did not want his men to be considered brigands.

Once it became obvious that there was to be no massacre or destruction of the town, people got over their initial fright and emerged from their homes to see this dusty spectacle. Children were everywhere, amazed to see so many men and riders in their town. Some of the raiders, missing their own children, interacted with the youngsters or gave out treats or other mementos. Jenkins and his men were the only show in town that night.

One thing that IS clear, Jenkins didn’t plan on remaining in Ohio any longer than necessary, and logic dictates he would proceed by the most direct route to the river, which would be down the street (past the old Elm Tree and Waid Cross’ Sons Grocery) to the levee which today still features a wide gravel beach extending a good distance down river.

The trick for the cavalrymen was getting to the other side safely – in the dark, and in unfamiliar terrain.

Old topographic maps show a small island along the opposite bank of the river perhaps a mile downstream from town roughly where the old locks and dam were located possibly indicating the presence of a ford, and a location called Elliott Landing downstream of that on the Virginia side.

“Here I proposed to recross the Ohio River, but a citizen familiar with the ford declared it impossible,” Jenkins wrote. Perhaps sensing a ruse and having already lost one soldier in the previous crossing, Jenkins insisted upon the citizen mounting a horse and personally leading the column over but saw that the water was too deep and that the horses would have to swim (a dangerous proposition in the dark when many of his riders could not swim).

He halted the column, and again with the assistance of his guide from Ravenswood, sought and found the course of the sand bar, and keeping upon its crest safely passed over, followed by the whole command along with their confiscated horses.

After the successful crossing, Jenkins reflected, “I entertained at the time, as I do now, the suspicion that it was the deliberate intention of the Yankee citizen to drown as many of the command as possible.”

As it was, once all the men were in the water and committed to crossing, the emboldened Home Guard resumed their harassing fire.

A little after midnight (September 5) we recrossed the Ohio at Racine, Sheffey recalled. The wildness of this rough crossing was heightened by the occasional flash of an Enfield on the Ohio bank, and the singing of the ball as it whistled over our heads, or skipped across the waters. They were very careful not to fire at us until all our men were in the water.

Once safely across the Ohio River, the cavalrymen proceeded a few miles where they camped for the night, ending a busy day for the 8th Virginia Cavalry Regiment, which started the day in Ripley, rode to Ravenswood where it spent most of the day, and then crossed the Ohio River twice.

Thus ended the First Confederate Invasion of Ohio.

Aftermath

The occupation of Racine, such as it was, didn’t amount to much – the entire exercise lasting only an hour or two. Although Jenkins earned some style points for “invading” Ohio, it was neither tactically nor strategically important (Jenkins and his opponents understood he could not permanently occupy Racine) and as an event it is hardly mentioned today except as the occasional footnote. It might be more accurate to call the event “Jenkins’ Shortcut” as opposed to “Jenkins’ Raid.”

Anywhere from a dozen to 25 horses were reported stolen, however Jenkins (who made detailed reports to his commander) didn’t report any horses being taken. Perhaps most telling, I could find no evidence of claims made to the federal government for damages resulting from his brief foray into Ohio. Contrary to a historical marker located in Star Mill Park, Racine was not the first northern town occupied by Confederate soldiers; that distinction belongs to Newburgh, Ind., which was the subject of a July 18, 1862, raid by a small group of partisans led by Confederate Col. Adam Rankin Johnson. However, Racine was the first town raided by Confederates in Ohio.

The

The local militia (and most “home guards” and militias during the Civil War for that matter) gave a dismal showing and were regularly routed or intimidated into inaction. However, Jenkins had speed and surprise in his favor. In retrospect, it was best to wait and fight another day. For Meigs County that day would come about 10 months later… and when that invader came the Home Guards so chastened by Jenkins’ men would be ready.

Perhaps shamed by their performance against Jenkins, and further honed by assisting in Col. Lightburn’s Retreat from the Kanawha Valley later that same month, the Home Guard (which was in the process of transforming into the Ohio Volunteer Militia, the forerunner to today’s Ohio National Guard) was prepared and determined to put a smarting on Gen. Morgan’s raiders the following July.

Jenkins went on to participate in Lee’s Invasion of Pennsylvania in June and July, 1863, and was injured in the Battle of Gettysburg. He died May 24, 1864, from injuries sustained in the Battle of Cloyds Mountain, Va., and was eventually buried in Spring Hill Cemetery in Huntington, W.Va.

Jenkins had three children, two daughters and a boy, through his marriage to Virginia Southard Bowlin. Their middle child, a daughter, Alberta Gallatin Jenkins (1861-1940), was adopted by her maternal grandfather and rose to fame as stage and film actress Alberta Gallatin.

Following Jenkins’ Route

Sadly, there is no historical trail marking the short path of Jenkins’ Raid through Ohio, but present-day county and state highways closely approximate the route, which is easy to follow.

Your tour begins at Washington’s Western Land Park and Museum, at 220 Riverfront Park, Ravenswood, W.Va. The museum is housed in the former Lock House of the U. S. Corps of Engineers Locks and Dam #22 on the banks of the Ohio River between the Ravenswood Bridge and Sandy Creek. The Museum building is owned by the city of Ravenswood, and its contents are owned and operated by the Jackson County Historical Society.

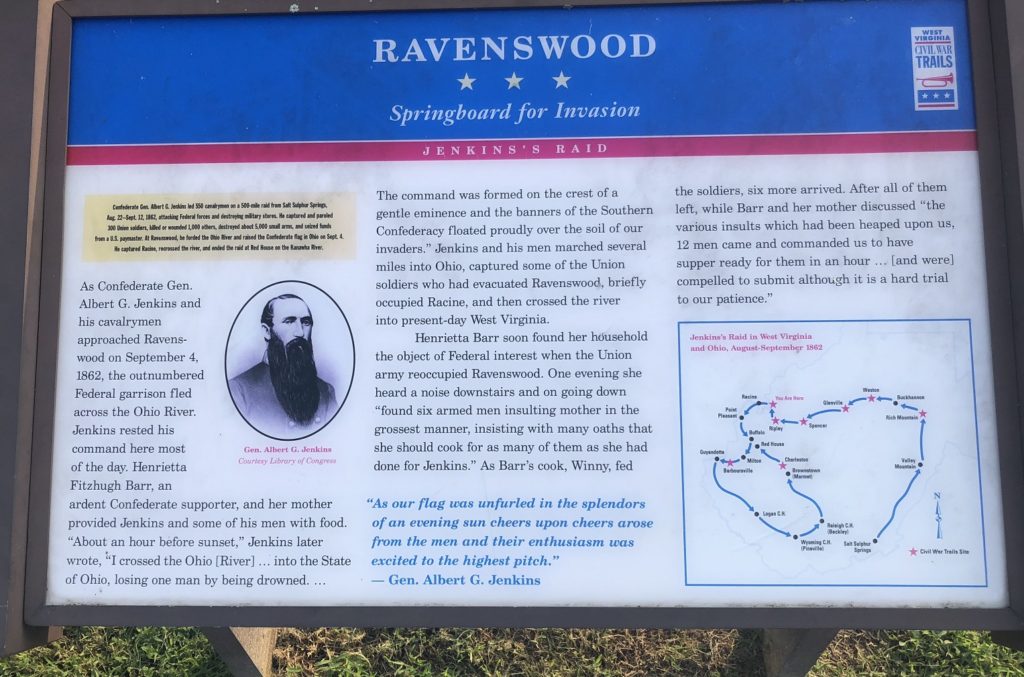

An informational marker in front of the museum, appropriately titled “Ravenswood: Springboard for Invasion” summarizes Jenkins’ Raid to that point, his occupation of Ravenswood, invasion of Ohio, and the aftermath of Jenkins’ visit to Ravenswood.

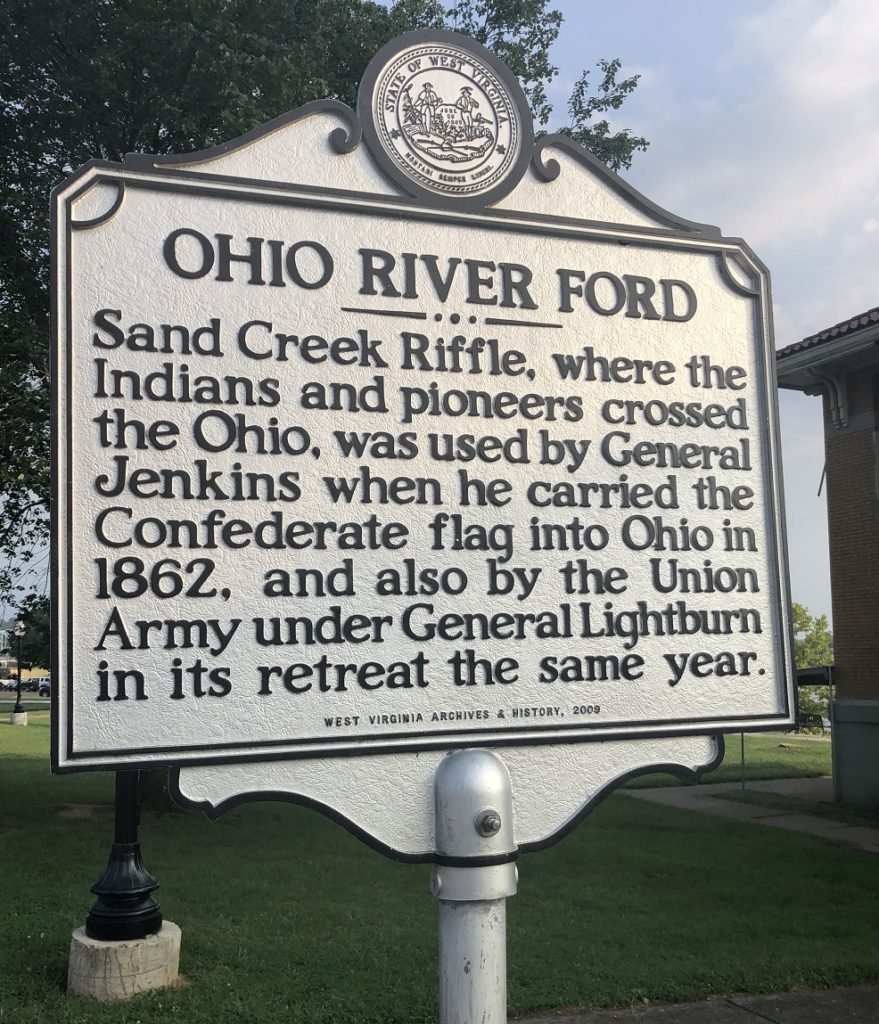

An adjacent historical marker identifies the site of Sand Creek Riffle and reads: “Ohio River Ford. Sand Creek Riffle, where the Indians and pioneers crossed the Ohio, was used by General Jenkins when he carried the Confederate flag into Ohio in 1862, and also used by the Union Army under General Lightburn in its retreat the same year.”

This is very near the location where General Jenkins crossed the Ohio River into Ohio.

As you cross the Ohio River on the William S. Ritchie Jr. Bridge (built in 1981) pay attention to the location of the state line on the bridge – this is approximately the point where Jenkins’ 8th Virginia Cavalry Regiment first set foot on Ohio soil. Once across the bridge, turn left on CR-338A (Great Bend Road). This closely approximates the route that Jenkins’ men would have traveled once crossing into Ohio, and where his men were amazed at the richness of the crops and horses in the state.

At the stop sign at the end of Great Bend Road, turn left on Ohio State Route 124 and go approximately a half mile then veer right onto CR124 (Tornado Road). It was during this stretch where Jenkins encountered isolated farms where citizens were cheering the Confederacy and Jefferson Davis, pleading to Jenkins not to burn down their houses or murder them. Turn left at the junction of CR124 and CR35 (Portland Road) to continue towards Racine.

As you enter Racine, CR124 becomes Elm Street. You’ll pass Southern Local Elementary School and High School, Oak Grove Road and then Tyree Boulevard on the left; this is where the raiders would have put the “home guard to flight” and entered the village proper.

In Racine there is little that remains of the town that was there in 1862. At the northeast corner of Star Mill Park a monument placed by Maj. Daniel McCook Circle 104, Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic reads “In memory of Jenkins’ Raid, First Confederate Invasion of the North, Racine, Ohio – September 4, 1862.”

At the corner of Elm and Third streets, one can stand near the spot where Jenkins’ men gathered under the old Elm Tree.

The historical marker there erected by the Racine Community in 1977 and entitled “Elm Tree” reads: “The Grand Old Elm grew on this site for centuries offering its many outstretched branches of majestic beauty and pleasant shade to generations of Indians long before the white man settled here. Children played in the abundant shade of the Old Elm and later in the roomy hollow trunk when only the bark and outer shell were still standing. Local fork often used a bench placed against the tree’s trunk to visit and wait for the street car that ran from Racine to Hobson. One of the largest trees ever grown in Ohio it reached a circumference of 28’ 8” – 3’ above the ground. The enormous trunk was cut down in 1929-1930 because of the danger caused by decay. To commemorate this well-known Elm is fitting for our country’s Bicentennial 1776-1976.”

To see where Jenkins’ men again crossed the Ohio River, go to the “Old Ferry Landing Park” at the end of Main Street. A lane there goes down to the river to the gravel bar which goes downstream nearly to the old locks and dam, which is where Jenkin’s men crossed the Ohio River via Wolf’s Bar into Virginia.

This concludes your journey retracing Confederate General Albert G. Jenkins’ route through Ohio.

Both of these monuments are inaccurate in different ways. The top monument at the Buffington Island State Memorial in Portland has the wrong date. The bottom monument in Racine’s Star Mill Park has the correct date, but incorrectly calls Jenkins’ Raid the “First Confederate invasion of the North.” The first Confederate invasion of the North occurred two months earlier in Indiana.

Other sources of information include era maps of Meigs County including that of H.H. Hardesty (1883), USGS topographical maps (1903), USDA aerial photos (1939), the Pomeroy Telegraph, the Wheeling Intelligencer, and Gallipolis Journal; and numerous online records of Jenkin’s Raid.