Joshua Gardner and the Fugitive Slave Case that went to the Supreme Court

Joshua Gardner and the Fugitive Slave Case that went to the Supreme Court

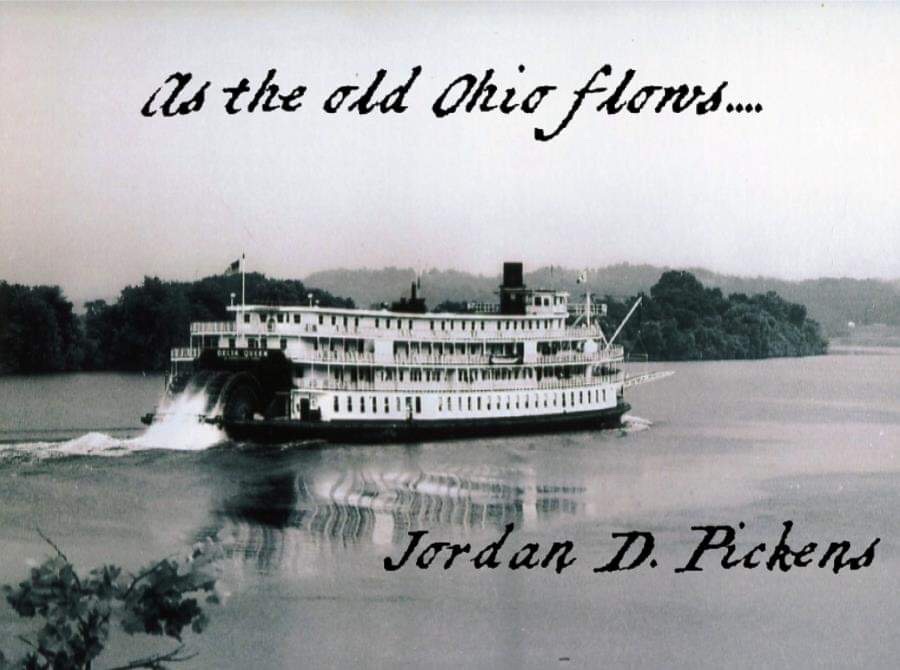

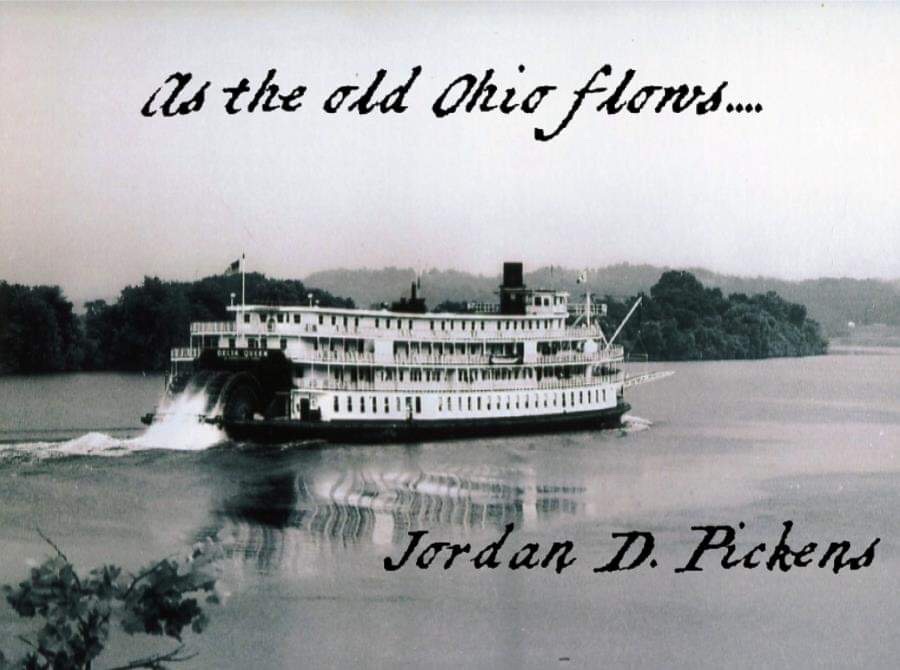

The Mason-Dixon Line was surveyed between 1763 and 1767 by Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon in the resolution of a border dispute involving Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware in Colonial America. Later (but before the Missouri Compromise) it became known as the border between the Northern United States and the Southern United States. The Ohio River is sometimes considered as the western extension of the Mason–Dixon Line. Due to the river being narrow, the Ohio was the way to freedom for thousands of slaves escaping to the North; many free black and whites helped the Underground Railroad resistance movement.In Meigs County, the Underground Railroad was in operation about 40 years prior to the start of the Civil War. Many of Meigs County’s early pioneers come from the New England area of the United States, among them hard-nosed abolitionists who hated slavery with a passion. It didn’t take long for these pioneers to help runaway slaves on their journey northward.

Caleb Gardiner was born November 1, 1763, married first Phoebe Gorton on March 30, 1786, and second Lydia Thurston on November 1, 1789, in Connecticut. He then moved to New York for a while some time after 1793 and finally moved to Rutland in 1803. His son Joshua Gardner was born on January 5, 1793, in Stonington, New London, Connecticut. 28 days after Meigs County was founded, he married Nancy Ann Caldwell on April 29, 1819, in Meigs County. According to Meigs County’s section of The Harris History, “”Many of the early settlers were of Puritan stock, and thoroughly imbued with the love of liberty, united to dauntless courage and daring to aid or rescue from oppression any helpless fellow being. Aiding escaping slaves came naturally to these people.”

The Wagner family had been one of the earliest settling in what is now Mason County, West Virginia, formerly Virginia. The Wagnersowned most of the land opposite of Pomeroy and kept over 100 slaves there. You could imagine the aggravation the Wagners felt when their slaves would escape across the river to Meigs County, especially after the growing hostility brought on by the kidnapping of Adam Smith in 1824 which fueled even more animosity on opposite sides of the Ohio River.

Joshua Gardner’s exploits as an Underground Railroader is certainly an interesting one, and it cost him everything he had. His son Albert C. Gardner repeated the following story as told to him by his father.

One morning in the early part of summer in 1825, a group of neighbors were at the blacksmith shop of Joseph Giles, near New Lima, among whom was Joshua Gardner, the father of Albert, who lived near. A horseman was seen approaching from the direction of Scipio, and as he came fully in view it was seen that a slave woman sat on the horse with the stranger. It was evident that she was not a willing passenger on that train, so they were promptly halted. Mr. Gardner demanded to know of the man’s authority in taking the woman.

He had none. The man said that “she acknowledged herself to be a slave of the Wagners in Virginia,” opposite Kerr’s Run in Ohio. She had made her escape from bondage and was on her way to Canada to join her husband, who had made the race for freedom some time before. Mr. Gardner told them that he was a peace officer, a town constable, and it was his duty to prevent kidnapping as well as other crimes. Turning to the woman, he asked her “if she wanted to go with this man.” She sobbed out, “No, sir.” Mr. Gardner told her to “get down and go where you please,” and as an officer of the law he would protect her. She slipped down from the horse and started to retrace the road from which she came.

The man started for Virginia to inform the Wagners and to put them on her track. Some of the party from the shop soon overtook the woman and guided her to the house of a Mr. Crandle, a poor man, but a noble citizen, who lived in an “out of the way” place, where she could be provided for until the search and excitement could die away. The colored woman was hidden in an old brush fence by a shelving rock, was fed, andwas well taken care of by Mrs. Crandle and family. The Wagners were soon in the neighborhood, scouring the country and offering rewards.

On one occasion a very poor man from the east side of the township came loitering around the Crandle’s premises in search of deer or turkey and discovered the hiding place of the woman. Tempted by the reward offered, he started to inform the slave owners, but first stopped at Stephen Ralph’s and told him of his plan and visions of future wealth. As soon as he left, Ralph shouldered his rifle and, marching through the woods, gave the alarm.

By the next morning a fire had destroyed the old brush fence and destroyed all traces of its recent occupant. The Wagners concluded the old hunter was a willful fraud. The woman was removed to the farm of Benjamin Bellows and secreted away until he had communicated with parties in Canada and ascertained the whereabouts of the woman’s husband. Mr. Bellows prepared a wagon with a false bottom, or double box. He put the woman in the bottom box and on the top a lot of Weaver’s reeds and started out for Canada to sell reeds. Mr. Bellows reported that he traveled one day with one of the Wagners and another party who were hunting this very woman, and that Mr. Wagner got off from his horse and helped Bellows’ wagon down a steep, rocky hill to keep it from turning over, little suspecting that the object of his search was so near him.

Foiled in all other points, the Wagners determined to try the law to obtain the value of their woman chattel from Joshua Gardner. Suit was brought in Court of Common Pleas at Chester and came to trial by jury, which resulted in a verdict for the plaintiffs. An appeal was taken, and the Supreme Court held that the admissions and sayings of the woman could not be admitted to prove her identity; if she was a competent witness, she must be produced in court, but if she was a slave, she could not be a competent witness. So the case failed. According to Marcus Bosworth, after the trial, Supreme Court Judge Pease was heard to say, “that an action of trover for the recovery of stock might do in Virginia, but it would not do in Ohio unless the stock had more than two legs.”

The next step was to kidnap Gardner and deal with him according to the rules of chivalry. It was reported that twelve men were seen on horseback in disguise for that purpose, but they were anticipated by a force abundantly able to resist them. There was no attack made. The expenses of this suit and trouble consequently consumed all of Mr. Gardner’s property. In 1849 he made an overland trip with the party called “The Buckeye Rovers” to California to recoup his fortune. He did and returned with enough gold dust to buy a comfortable home in Rutland, Ohio, where he enjoyed the respect and confidence of his neighbors until he was 77 years old. He died March 1, 1869 in Rutland.

As the old Ohio flows….