Recalling cholera epedemics in Meigs County

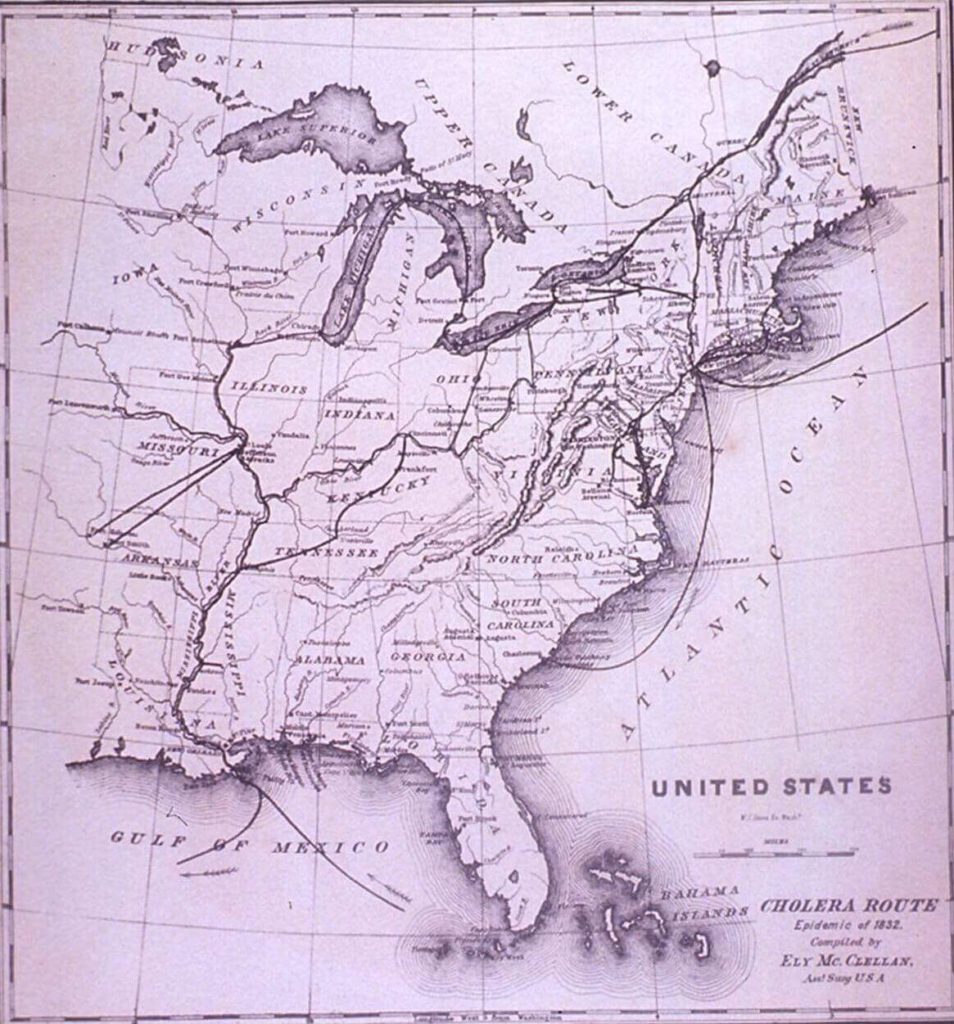

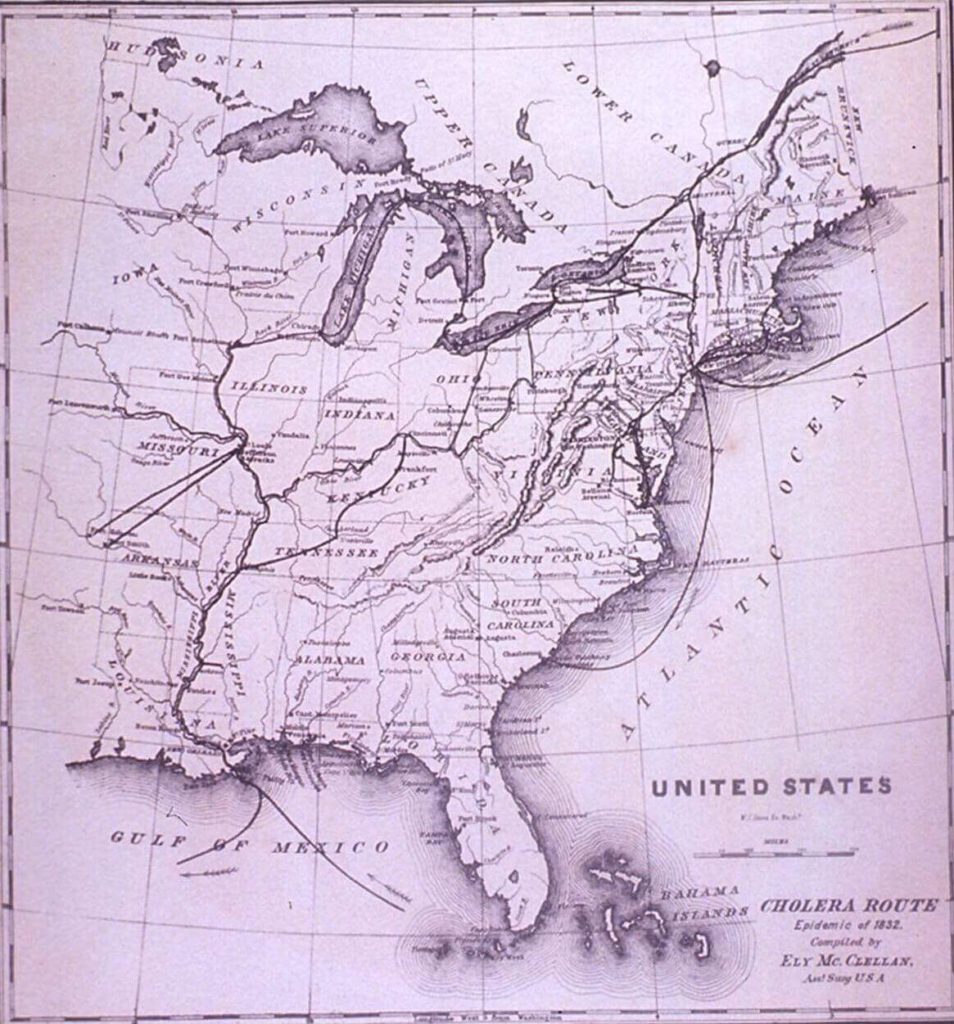

Cholera Route of the Epedemic of 1832.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” – George Santayana. How, you may ask? A fine example today is the hepatitis A epidemic you see happening in the news at fast food restaurants all around our region. What causes this disease to be transmitted? According to an article in an April edition of the Dayton Daily News, “Hepatitis A is a vaccine-preventable, communicable disease of the liver caused by the hepatitis A virus . . . . It is usually transmitted person-to-person through contact with an infected person’s stool, or consumption of contaminated food or water.” In other words, unsanitary health practices.

Looking back to the first half of the 19th century, the world had another epidemic from unsanitary health practices: cholera. According to Webster’s Dictionary, cholera is “an infectious and often fatal bacterial disease of the small intestine, typically contracted from infected water supplies and causing severe vomiting and diarrhea.” It is spread mostly by unsafe water and unsafe food that has been contaminated with human feces containing the bacteria. Meigs County fell subject to not one, but two, epidemics over a fifteen year span, one in 1834 and the other in 1849.

Cholera first appeared in the United States in 1832, most likely from European immigrants due to the first cases being reported in New York and New Orleans where many were arriving. In Ohio, the city of Cleveland reported the first death from the disease. That same year, the first recorded Meigs County citizen died of the disease. Barzillai Hosmer Miles, a minister from Rutland, died of cholera while returning from Louisiana to Meigs County. While the location of Barzillai’s grave is not known, it was ironic that his family owned the land that eventually became Miles Cemetery where his father John Miles was buried years later.

The year before the first major cholera outbreak in Meigs County, a steamboat approached a household in Lebanon Township, seeking permission to bury a man from the boat in the small nearby graveyard. The request was rudely denied due to the home owner’s fear of cholera, and the man was interred along the roadside instead.

The first of countless reported cases of cholera in Meigs County occurred in July of 1834. Doctor James S. Hibbard was called from Chester to Syracuse to tend to a man who had been returned from a steamboat trip and was sick with severe vomiting and diarrhea. Larkin’s Pioneer of History of Meigs County states:

Dr. Hibbard pronounced the case cholera and prescribed accordingly. On his way back to Chester he was attacked with the malady and, getting off from his horse, took a dose of calomel, lay down by the roadside and fell asleep in the woods. As soon as he was able to remount his horse he proceeded homeward. He finally recovered.”

That same year, six year old Marcus Bosworth, Jr., “went to bed as usual, but later called his mother, ‘so very sick,’ and, although medicine was administered at once, by 10 o’clock the child was dead.” (Larkin) The epidemic was so severe that Van Weldon, a local cabinet maker, had to switch from making cabinets to making coffins for the victims of the epidemic. Downriver at Cincinnati, as a preventative measure, the burning of coal, delivered from Pomeroy, on every street corner gave hope that it would stop the disease from spreading.

During the second epidemic in 1849, several cholera deaths were noted in Pomeroy and Letart; however, the first reported deaths from cholera in that year were in the Bailey family of Middleport. Cholera claimed the lives of David Bailey and his wife, his daughter and son-in-law, and David’s sister Mrs. Hudson. According to The Autobiography of Dr. Thomas H. Barton, The Self-Made Physician of Syracuse, Ohio, “The smoke of tobacco was regarded as a preventative and many persons, even women and small boys, had cigars almost constantly in their mouths. Others placed full confidence in garlic…some chewed it constantly, others kept it in their pockets and shoes. Even the time honored custom of hand shaking fell into disrepute and many recoiled with affright at even the [offer] of a hand.”

In Columbus, 116 inmates at the Ohio Penitentiary succumbed to the illness. Former President James Polk, a resident of Tennessee, was the most famous person to die of cholera in 1849. Cholera resulted in the postponement of the first Ohio State Fair and the Ohio Constitutional Convention of 1850-1851. 8,000 people in Cincinnati died in this epidemic, including Harriet Beecher Stowe’s infant son.

Unfortunately for people stricken with cholera, the treatment was almost as bad as the illness. Doctors routinely prescribed calomel for cholera victims. Calomel contained mercury, and numerous people died from mercury poisoning or suffered other ill effects from this drug. As sanitation improved within the United States, including chlorination of water, the illness became less common. The standard treatment for cholera today is to keep the ill person hydrated with germ-free water or other fluids… none of which include mercury.

As the old Ohio flows….