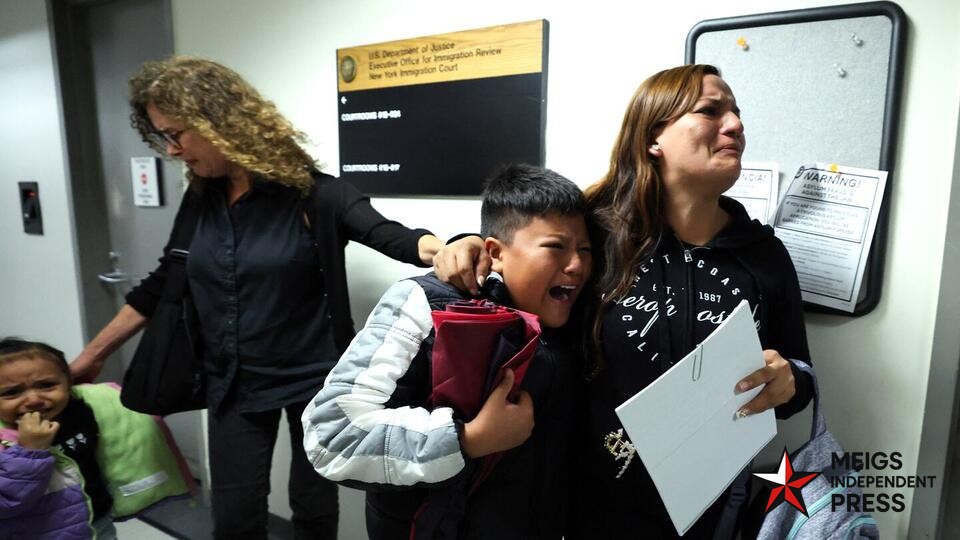

A 9-year-old stood beside her mother and infant brother in a Manhattan courthouse hallway earlier this month, pounding the wall and sobbing as federal immigration agents took her father into custody after a routine hearing. In the aftermath, the fourth grader from Venezuela—who manages epilepsy—was too grief-stricken to return to class. Her mother, who asked that their names be withheld to avoid drawing attention from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), said the girl repeatedly insisted she was too exhausted to go and cried so often she worried it would trigger seizures.

One refuge emerged amid the turmoil: their small, close-knit West Village public school. At the family’s request, Chalkbeat is not identifying the school. The principal offered to meet the child at the homeless shelter where the family was staying and walk her to campus. A teacher phoned to tell the girl her classmates were anxious to see her. Parents connected the family to attorneys and advocates. The mother said in Spanish that the school had been constantly present—encouraging her daughter to return, helping calm her, and looking out for the baby too.

No one knows exactly how many New York City public school parents have been detained during President Donald Trump’s intensifying deportation efforts. The Deportation Data Project’s ICE figures do not indicate whether detained individuals have children. But as arrests have climbed, so have wrenching scenes of parents being separated from their families—often amid screams—in the corridors of Manhattan’s immigration court at 26 Federal Plaza.

Educators and advocates say a growing number of schools have become essential lifelines for students whose caregivers have been detained, working to stabilize home lives, maintain academic progress, and help children process fresh trauma. The ripple effects have tested entire school communities.

At Central Park East II, a combined middle and high school in Manhattan, the recent detention of a parent with two enrolled children deeply unsettled staff, Principal Naomi Smith said. “It’s really hard,” she noted, describing how adults who knew the mother or taught her kids felt shaken.

For families caught in ICE proceedings, immediate concerns often center on who will pick up children and make decisions in a parent’s absence, said Julie Babayeva, a supervising attorney at the New York Legal Assistance Group. Many parents fear their young kids will be stranded at school on the day of an arrest.

New York law allows immigrant parents to designate a standby guardian who can step in if they’re detained or deported, making educational decisions and helping keep students enrolled. Yet awareness of the law is uneven, Babayeva said, prompting schools to host workshops where families can complete paperwork and learn their rights. In one instance, a local public school parent who is a U.S. citizen called Babayeva’s hotline offering to serve as a guardian for immigrant children at his own children’s school.

Schools have also mobilized tangible support. At Central Park East II, staff and families raised money so the detained mother could afford phone calls from the detention center, Smith said. They also assembled a bag with clothing and essentials in case of deportation. At ELLIS Preparatory Academy, a Bronx high school serving newly arrived immigrant students, a teenager lost her primary child care for her toddler when her mother was arrested in June. Principal Norma Vega offered to watch the toddler in her office so the student could attend summer school, though the girl ultimately declined.

If the city learns of a parent’s arrest and the family consents, officials connect them to organizations that provide legal support, said Education Department spokesperson Dominique Ellison.

School-based mental health teams are doing more than ever to help children cope, offering extra time with counselors and social workers. But addressing trauma in real time is difficult, said Jessica Chock-Goldman, a Manhattan school social worker who has supported students with detained parents. She emphasized that many families are still in the midst of crisis: “You can’t process something you’re currently living through.” Even so, Chock-Goldman said she’s continually struck by the resilience of students and caregivers navigating constant fear.

For the Venezuelan fourth grader in Manhattan, the school’s persistent outreach made a difference. She returned eight days after her father’s arrest. The walk to school is still painful—she used to make it with her dad—but being back in the classroom has lifted her mood, her mother said.

Not every effort succeeds. At one Manhattan high school, a student whose parent was detained last year had no remaining adult guardians in the country. Despite attempts to keep in touch, the school lost contact, the principal said. The student did not return this fall.

Reporting by Michael Elsen-Rooney for Chalkbeat New York.

Leave a Reply