Freedom, William Nelson and Lincoln Hill

free·dom (noun) – The power or right to act, speak, or think as one wantswithout hindrance or restraint; absence of subjection to foreign domination or despotic government; the state of not being imprisoned or enslaved.

We enjoy many freedoms as citizens of the United States of Americathanks to our strong military which keeps us free. But for slaves in America, that wasn’t always the case. Imagine trading in a bucket of turtle eggs to gain you your freedom.

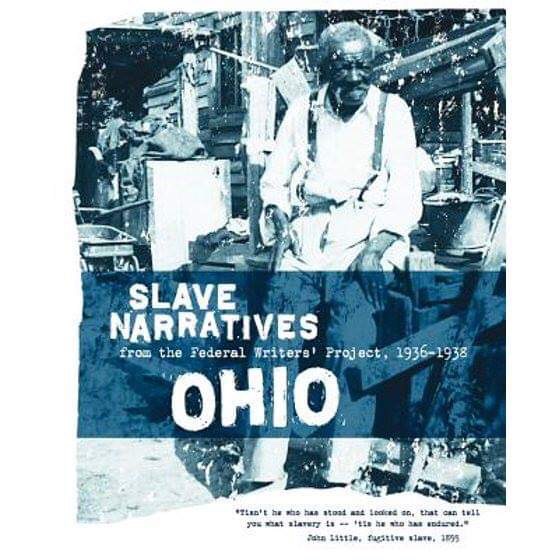

The year is 1937. Meigs County is recovering from the second worst flood in recorded history; the Great Depression’s effects are still being felt around the country, although President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal is easing the strain. The Federal Writers’ Project had been created in 1935 as part of the United States Work Progress Administration to provide employment for historians, teachers, writers, librarians, and other white-collar workers. Originally, the purpose of the project was to produce a series of sectional guide books under the name American Guide, focusing on the scenic, historical, cultural, and economic resources of the United States.

William Nelson, of Meigs County, was interviewed by a worker for the Ohio Federal Writer’s Project in 1937. In this transcript of the interview, Nelson talks about running away from the southern plantation where he was a slave and heading north to freedom. He refers to President Abraham Lincoln as a “Saint of the colored race.” In the transposition, author and editor Audrey Meighen chose to write in “Black English”dialect, which is written to portray how Mr. Nelson spoke when interviewed by Sarah Probst, the reporter for this project. Mr. Nelson was 88 at the time of this interview.

Whar’s I Bawned? ‘Way down Belmont Missouri, jes’ cross frumC’lmubs Kentucky on de Mississippi. Oh, I ‘lows ‘twuz about 1848, caise I wuz fo’teen when Marse ben done brung me up to de North home with him in 1862.”

“My Pappy, he wuz ‘Kaintuck’, John Nelson an’ my mammy wuzJunis Nelson. No sah, I don’t know whar dey wuz bawned, first I member ‘boutwuz my pappy building railroad in Belmont. Yes suh, I had five sistahs and brutchaha. Der names – lets see – Oh yes – der wuz, John, Jim, George, Susan, and Ida. No, I don’t member nothin’ ‘bout my gran’parents.”

“My mammy had her own cabin for hur an us chillums. De wuz rails stuck through de cracks in de logs fo’ beds with straw on top fo’ to sleep on.”

“What’d I do, down dar on plantashun? I hoedcorn, tatahs, garden onions, and happed take caie de hosses, mules an oxen. Say-I could onions goin’ backwards. Yessuh, I cud.”

“De first money I see wuz what I got from sum soljers fo’ sellin’ dema buket of turtl’ eggs. Dat wuz de day I run away to see sum Yankee steamboats filled with soljers.”

“Marse Dick, Marse Beckwith’s son used to go fishin’ woth me. Wunce we ketched a fish so big it tuk three men to tote it home. Yes suh, we always had pleant to eat. What’d I like best? Corn pone, ham, bacon, chickens, ducks and possum. My mammy had her own garden. In de summah men folks weah overalls, and de womins weah cotton and all of us went barefooted. In de winter we wore shoes made on de plantashun. I wuzn’t married ‘till aftah I come up North to Ohio.”

“Der wuz Marae Beckwith, mighty mean ol’ debel; Miss Lucy, his wife and de chillums, Miss Manda, Miss Nan, and Marse Dick, and the other son wuz killed in de war at Belmont. Deir hous’ wuz big and had two stories and porticoes an den de Marse Beckwith owned land with cabins on ‘em whar de slaves lived.”

“No suh, we didn’t hab no diriver, ol’ Marse dun his own drivin’. He was a mean ol’ debel and whipped his slaves of’n and hard. He’d make ‘em strip to the waist then he’d lash ‘em with his long black snake whip. Ol’ Marse he’s whip womin same as men. I member seein’ ‘im whip my mammy once. Marse Beckwith used the big smoke hous’ for de jail. I meber see no slaves sold but I have seed ‘em loaned and traded off.”

“I member one time a slave named Tom and his wife, my mammy an’ metried to run away. But we’s ketched and brung back. Ol’ Marse whipped Tom and my mammy and sent Tom off on a boat.”

“One day a white man tol’ us der waz a war and sum day we’d be free.”

“I neber heard of no ‘ligion, baptizin’, nor God, nor heaven, de Bible, nor education down on de plantashun, I gues’ dey didn’t hab none of em. When Marse Ben brung me north to Ohio with him wuz de first time I knowed ‘bout such things. Marse Ben and Miss Lucy mighty good to me, sent me to school and told me ‘bout God and Heaven and took me to Church. No, de white folks down dar neber hepped me to read or write.”

“The slaves wuz always tiahed when dey got wurk dun in the evenins’ so dey usually went to bed early early so dey’d be up fo’ clock next mornin’. On Christmas Day dey always had big dinnah but no tree or gifts.”

“How’d I cum North? Well, one day I run ‘way frum plantashun and hunted ‘till I filled a bucket full turtl’ eggs den I takes dem ovah on river whar I hears der’s sum Yankee soljers and de soljers buyed my eggs and hepped me on board de boat. Den Marse Ben, he wuz yankee ofser, tol ‘emhe take care of me and he did. Den Marse Ben got sick and cum home and brung me along and I staid with ‘em ‘til I wuz ‘bout fo’ty when I gets married an moved to Wyllia Hill. My wife, was Mary Williams, but she died long time ‘go an so did our little son, since dat time, I’ve lived alone.”

“Yessuh, I’se read ‘bout Booker Washington.”

“I think Abraham Lincoln wuz a mighty fine man. He is de ‘Saint of de colured race’.”

“Good day suh.”

Indeed, Abraham Lincoln was loved by many in Meigs County, so much that on July, 18, 1860, a political rally and flag raising was held on Heckard’s Hill in Pomeroy to support Abraham Lincoln for President of the United States. The hill was renamed Lincoln Hill and has been called that ever since. Ten years prior to re-naming Heckard’s Hill to Lincoln Hill, in 1850, it began as a community for free blacks. The community included its own school and church.

As the old Ohio flows….